In Defense of Paxlovid

A counterpoint that acknowledges the medicine’s shortcomings, yet is short on viral outrage

Disclosure: I receive no compensation from Pfizer or even free lunches from drug representatives.

I feel the need to get Paxlovid’s back. The antiviral medicine for Covid has served us well. As a primary care doctor who has seen the worst of what this disease can do to people, and who has followed the medical literature, experts, and consensus guidelines since this whole thing started, I’m disappointed by the current trashing of this medicine. So I’m going to briefly review a recent study that resulted in some prominent physicians throwing shade on Paxlovid, a lot of doctors leaving mea culpas and scornful comments on public websites, and the general blowing of wind into the sails of people who hate on doctors anyway, but are ready to sell you something else. We will then touch on several of the many other studies showing benefits. And finally I’ll lay out what my goals are when I recommend Paxlovid to patients… and just like them, everyone should have the personal autonomy to reply: let’s do this, or no thanks.

This is a long post of 3,000 words. It will take 10 minutes to read, so come back if you don’t have time right now. See if you can find the hidden albatross, too.

The recent study

The prestigious New England Journal of Medicine published a small study two weeks ago which found that Paxlovid did not clear every symptom of Covid infection much faster than placebo in 1,288 lower risk people randomized to treatment or placebo. This was based on data from what’s called the EPIC-SR study.

Ok. So in lower risk individuals, taking Paxlovid won’t clear up some combination of cough, shortness of breath, difficulty breathing, feeling feverish, chills or shivering, muscle or body aches, diarrhea, nausea, vomiting, headache, sore throat, and stuffy or runny nose faster than placebo. But we already knew that from previous evidence. I don’t tell people they will feel better faster with Paxlovid, although anecdotally many do improve drastically. Instead I am looking to further reduce the risk of severe disease, hospitalization, and death in higher risk individuals, and to reduce the risk of long Covid in anyone who wants to bet on that. Recall that people in their late 30’s to early 50’s are the most likely to develop long Covid, and have a lot to lose when they can’t think well, breathe well, or exercise well anymore. Yes, I still see this very commonly. For many people there is a cumulative toll taken with repeated infections.

Considering the limited scope and conclusions of this study about symptoms in lower risk people, I would have thought the reaction would have been kind of ho hum. Yet even a contributing editor to the NEJM penned a piece about “The Rise and Fall of Paxlovid,” and recapped “the astonishing success and now failure of this intervention.”

Really?

Here are some weaknesses of this newly published study, which was already weak in its primary endpoint of just symptom reduction:

Participants were considered “treated with Paxlovid” even if they took just 1 pill. 1 pill total.

The study’s definition of “symptom resolution” means that if someone stated they had mild nasal congestion among other symptoms at the start of treatment and then continued to report mild nasal congestion (despite a potential resolution of shortness of breath, cough, fever, and diarrhea), that mild yet persistent nasal congestion would be enough to disqualify any improvement they had overall.

The definition of “standard risk” patients would lump together an unvaccinated 18-year-old and a vaccinated 89-year-old into the same lower risk category (shout out to Dr. Michael Osterholm for this). However…

Only 5% of participants were over age 65. Less than 2% had heart or lung disease. So they were pretty healthy people overall. But this kind of population represents a small minority of the patients we see in real life examining rooms, and once again undermines the applicability of this study at the point of care.

You may recall my ninja tricks for statistical analysis, so here’s an application. In this study of mostly healthy, young-ish people (average age of 42) treated with Paxlovid, there was a 50% relative risk reduction in hospitalization and death… but since these outcomes are now thankfully rare in low risk people, this equated to only a 0.8% absolute risk reduction. Haters loved this. The study was too small for this 50% RRR or 0.8% ARR to reach statististical significance. But I would argue that the point of offering treatment to lower risk people, like those 35-50 year olds (the age group most likely to develop long Covid) for example, would be to potentially reduce long Covid incidence. And I have consistently posited that lowering viral loads (which Paxlovid given early can do by 90%) will reduce cumulative damage to the cardiovascular, nervous, and immune systems, among all the other systems this systemic disease can harm. Helping our immune systems more fully clear this virus should also help reduce the subset of long Covid patients who have been shown to incompletely clear this coronavirus. Waiting 5, 10, 15 years for an impossible randomized trial to prove this stuff is folly. We are allowed to use intuition in such circumstances, and to accept that while we may be wrong, evidence cited below points us towards indirect proof of concept.

And here’s some more of dem apples:

A small subgroup analysis in this already small study looked at high-risk but vaccinated patients. Even though the small sample size limited statistical significance, if we still play with the numbers, about 47 people in this group would need to be treated with Paxlovid to avoid one hospitalization or death. That’s not too shabby actually, considering these folks were defined as “standard risk.” Do you know how sick you have to be to get admitted to a hospital these days? There is a lot of suffering short of hospitalization to alleviate, too.

The authors also found “the mean number of days in the hospital per 100 participants was 5 in the Paxlovid group and 18 in the placebo group. The longest hospital stay was 9 days in the Paxlovid group and 32 days in the placebo group.”

I affirm that using Paxlovid in low risk patients to avoid hospitalization and death is an expensive proposition, likely to induce a lot of side effects and some adverse effects. But what about long Covid? What about reducing cumulative damage each time we get Covid? What about treating for 10 days versus 5? Is there evidence to answer these questions, or to at least give us a clue? Read on.

Being an upstander for Paxlovid

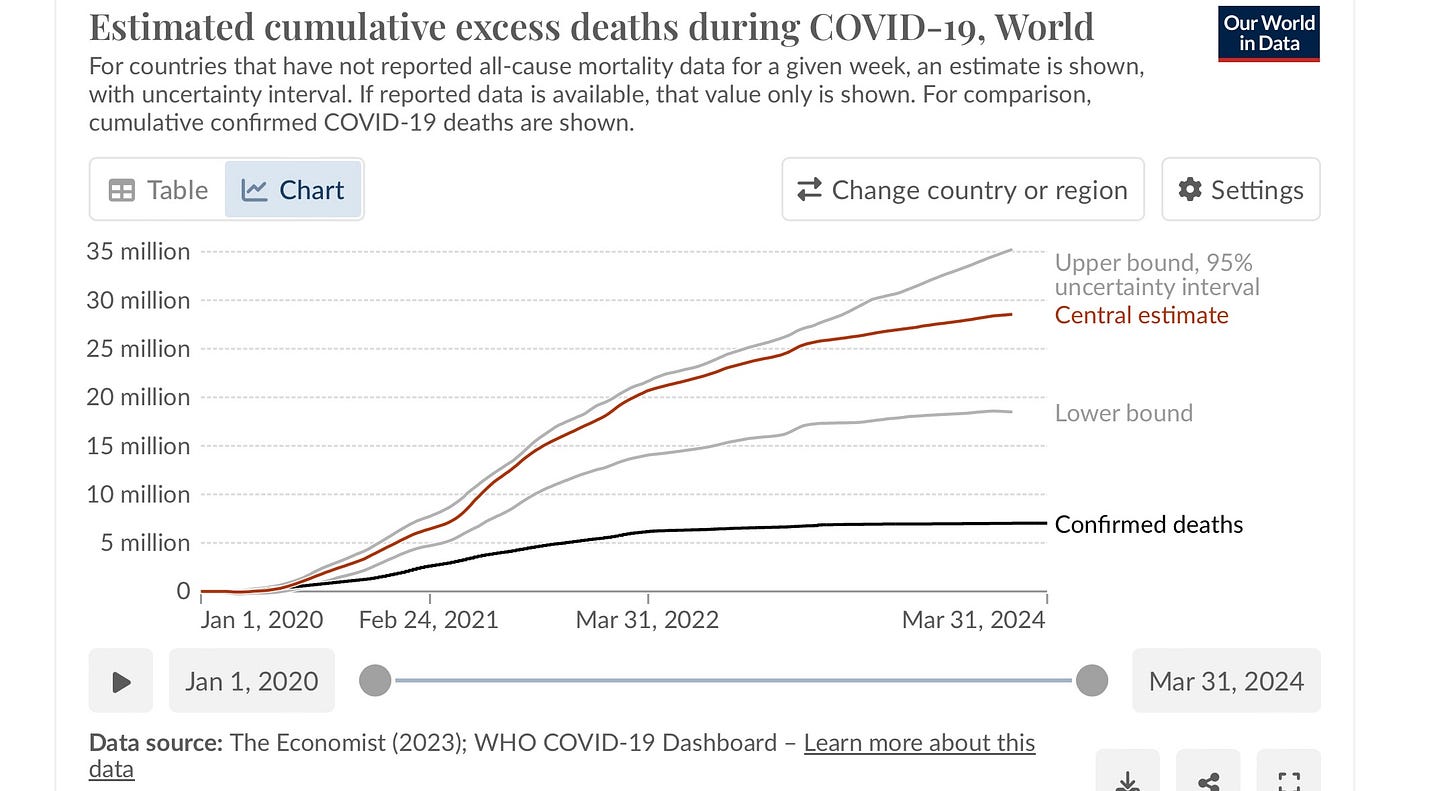

Are we to throw out a medicine that reduced hospitalization and death by 90% before vaccines were available? Did the mechanism of action change? Of course not. Has SARS CoV-2 developed antiviral resistance? Nope. Did the chance of dying from Covid decrease? Absolutely. Thanks to vaccines and the magic of our immune systems. Yet the excess mortality in the world since 2020 suggests that about 30 million mothers, fathers, grandparents, aunts, uncles, and young people have died from Covid. This kind of statistic captures all the increased death, including after people have recovered from the acute infection. The real toll keeps churning on, reducing life expectancy, and looking like this:

Look at that flat black line of “confirmed deaths.” No wonder most people think this thing is over. They don’t associate the stroke 3 months later with the previous Covid infection. Yet this winter we still had a steady loss directly from Covid of about 2,000 Americans per week. That was a 9/11/2001 twin tower event every 10 days.

Other Paxlovid studies, lest we forget

Additional findings from this same symptom-based EPIC-SR study of vaccinated + unvaccinated, low risk people with Covid were previously published, too. Pfizer stopped enrolling new patients when it became clear that in these relatively healthy people, with some combination of vaccination and previous infection, severe disease as manifested by hospitalization and death was rare. Nonetheless, in 2022 we learned from this same data set that treatment with Paxlovid resulted in a 62% decrease in Covid-related medical visits per day across all patients. There was a 72% reduction in the average number of days in the hospital among Paxlovid-treated patients versus placebo.

The EPIC-HR trial enrolled nonhospitalized adults with mild to moderate COVID-19 who were not vaccinated and who were at high risk of progressing to severe disease. The trial demonstrated that starting Paxlovid within 5 days of symptom onset reduced the risk of hospitalization or death through day 28 by 89% compared to placebo. This was the gold standard study result that had us celebrating. Remember that?

The CDC released a Morbidity and Mortality Report over a year ago:

This study analyzed a large electronic health record data set to assess the association between receiving a prescription for the oral antiviral treatment Paxlovid and hospitalization with Covid within 30 days among eligible U.S. adults during April-August 2022, adjusting for demographic factors, geographic location, vaccination status, previous infection, and underlying health conditions.

Among 699,848 eligible adults, 28.4% received Paxlovid within 5 days of diagnosis, and Paxlovid prescription was associated with a 51% lower hospitalization rate overall, including a 50% lower rate among those who had received 3 or more mRNA vaccine doses and lower rates across all adult age groups.

The findings demonstrate that Paxlovid provides protection against severe Covid outcomes among eligible persons, including those with previous immunity from infection or vaccination, and Paxlovid should be offered to eligible adults, especially groups at highest risk like older adults and those with multiple underlying conditions.

A 2023 study funded by the CDC and NIH, with data from the Kaiser Permanente health system, published in The Lancet:

In this matched observational outpatient cohort study, data was extracted from electronic health records of non-hospitalized patients aged 12 years or older who received a positive SARS-CoV-2 PCR test result between April 8 and October 7, 2022, comparing outcomes between those who received nirmatrelvir–ritonavir and those who did not.

Nirmatrelvir–ritonavir had an overall estimated effectiveness of 54% in preventing hospital admission or death within 30 days of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test, which increased to 80% when dispensed within 5 days of symptom onset, and 90% when dispensed on the day of testing within 5 days of symptom onset.

In a setting with high levels of Covid vaccine uptake, Paxlovid effectively reduced the risk of hospital admission or death within 30 days of a positive outpatient SARS-CoV-2 test.

A new National Institutes of Health study preprint using data between December 2021 and February 2023:

This was a multi-institute retrospective cohort study of 1,012,910 patients.

The results showed that Paxlovid treatment reduced 28-day hospitalization by 26% and mortality by 73% compared to no Paxlovid treatment within 5 days, though overall Paxlovid uptake was low at just 9.7%.

The study concluded that in Paxlovid-eligible patients, treatment was associated with decreased risk of hospitalization and death, supporting the real-world effectiveness of Paxlovid.

If uptake had been 50%, nearly 48,000 deaths could have been prevented during that time.

You get the idea. But in case more evidence needed: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9

Addendum 7/2024:

Paxlovid keeps working, especially for higher risk people and when started early

This study published last month in The Lancet found that even in 2022, with a combination of previous infections and vaccinations, Paxlovid is still worth taking:

In this matched cohort study of data from a large, integrated US health-care system, receipt of nirmatrelvir–ritonavir within 5 days of symptom onset was 80% effective in reducing the risk of hospital admission or death within 30 days of an outpatient positive SARS-CoV-2 test.

Irrespective of time of dispensing (within 5 days or not), nirmatrelvir–ritonavir was 54% effective in reducing the risk of hospital admission or death within 30 days.

To our knowledge, our study is one of the first large real-world effectiveness studies done during the BA.2 and BA.4 and BA.5 omicron waves in a broad representative patient population of mostly vaccinated adults that includes people younger than 65 years.

And when patients were tested and started treatment the same day, reduction in hospitalization and death was up to 90%.

Addendum, 12/2024

Protection against hospitalization and death in adults receiving Paxlovid plus faster resolution of symptoms and lower use of healthcare resources

An authoritative randomized clinical trial published in Clinical Infectious Diseases demonstrated that Paxlovid significantly reduced Covid hospitalizations, deaths, and healthcare resource utilization compared to placebo during the Delta period from July 2021 through December 2021. In the nearly 2,000 patients randomized, those given Paxlovid had an 85.5% reduction in hospitalizations, faster symptom resolution (median 16 vs 19 days), and zero deaths in the Paxlovid group compared to 15 deaths in the placebo group over 6 months.

Do Paxlovid or other antivirals reduce the risks of long Covid?

(and other nasty sequelae of infection like that increased all cause mortality we are still seeing in the world, subsequent cardiovascular events, higher dementia rates, lowering of IQ, Parkinson’s, higher autoimmune disease onset, etc)?

I wish we had a prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled clinical trial to answer this question. It would be great if researchers used biomarkers, biopsy results, and imaging studies to look at before and after, with or without. But if you think of the impossible logistics of setting this up, the mild clinical cases of Covid that are not counted, the controlling for a million variables and behaviors, the opaque nature of what’s going on under the hood when we are sick, the reliance on symptoms over biomarkers, and then funding the whole albatross for 5-10 years… it’s just not going to happen.

But we do have these studies:

A systematic review and meta-analysis of nine observational studies published in The Journal of Infection in June, 2024 showed an overall ~25% reduction in long Covid rates for people treated with Paxlovid during acute infection. The details:

Early use of oral antivirals reduced the risk of long COVID by 23% overall.

(nirmatrelvir-ritonavir) appeared to perform better than molnupiravir:

- Paxlovid reduced risk by 24%

- Molnupiravir reduced risk by 12%

The analysis included 866,066 non-hospitalized patients across nine studies.

Early use was generally defined as within 5 days of COVID-19 diagnosis.

Long COVID definitions varied, with some studies measuring outcomes at 30 days post-diagnosis and others at 90 days.

The protective effect was observed regardless of age or sex.

The findings suggest that broader use of antivirals could be considered to prevent long COVID, particularly in light of its high incidence rates (10-30% in non-hospitalized patients, 50-70% in hospitalized patients).

The authors hypothesize that antivirals' ability to lower viral replication rates may contribute to reducing long COVID risk.

The study emphasizes the importance of timely antiviral intervention in mitigating long-term COVID-19 effects.

A study published in JAMA Internal Medicine in June of 2023:

This cohort study used the health care databases of the US Department of Veterans Affairs (VA) to identify patients who had a SARS-CoV-2 positive test result between January 3, 2022, and December 31, 2022, and compared those who were treated with oral Paxlovid within 5 days after the positive test (n = 35,717) with those who received no antiviral or antibody treatment (control group, n = 246,076).

Paxlovid was associated with 26% less risk of long Covid, 48% less risk of post-acute death, and 30% less risk of post-acute hospitalization. The absolute risk reduction was 2.32, 0.28, and 1.09 less cases of PASC, post-acute death, and post-acute hospitalization for every 100 treated persons between 30 to 90 days of infection. Not amazing, but statistically significant.

These were older veterans, mostly white, male and average age of 62. This demographic develops long Covid at lower rates than 40 something men and especially women. Previous data from the CDC Household Pulse Survey estimated that around 15-20% of 40 to 60 years olds had ever experienced long Covid symptoms, versus just 5-10% of those 60 and up like the ones studied herein. So the potential benefit for preventing long Covid in middle aged persons should be expected to be greater than what was found here.

The study concluded that treatment with nirmatrelvir during the acute phase of COVID-19 may reduce the risk of post-acute adverse health outcomes, including long Covid, across the risk spectrum and regardless of vaccination status and history of prior infection.

In October 2023, researchers from the National Library of Medicine and the National Institutes of Health (NIH), also published in JAMA Internal Medicine, looked at Paxlovid and molnupiravir (another antiviral). They found a smaller relative risk reduction for long Covid in Medicare enrollees:

The study was a cohort study of Medicare enrollees aged 65 years or older diagnosed with Covid-19 between January and September 2022, examining the effects of Paxlovid and molnupiravir on the incidence of post-Covid condition (PCC).

The results showed that the incidence of PCC was

11.8% for patients receiving Paxlovid (13% relative risk reduction)

13.7% for molnupiravir (8% risk reduction)

14.5% for neither

Recall once again that older age groups are diagnosed with long Covid less frequently than younger/middle aged groups

A survey of people done by UCSF researchers and published in January 2024 found no benefit for preventing long Covid, but had potential respondent bias and methodological fails in my opinion:

Only a third of study participants responded to the long-Covid survey. People who opted to take Paxlovid might have been sicker than people who didn’t, and severity of illness is correlated with higher risk of long Covid. Therefore sicker patients opted to take Paxlovid, and may have obscured any protective effect in general.

People opting to take Paxlovid might also be more aware and vigilant for symptoms of long Covid developing.

The survey didn’t include the option to report symptoms like brain fog or post exertional malaise, two of the more common and debilitating long covid symptoms. Survey participants were only given the chance to select symptoms like fever, nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea- which are not common long Covid symptoms at all.

There were no objective criteria evaluated, just subjective self reports.

Addendum 11/2024. A Dubai-based retrospective cohort study published in Nature Scientific Reports analyzed electronic health records from 7,290 COVID-19 patients (672 receiving Paxlovid, 6,618 without antivirals) between May 2022 and April 2023 to assess Paxlovid's impact on hospitalization and long COVID rates, with long COVID defined as symptoms persisting or emerging 28+ days post-infection.

After adjusting for factors, Paxlovid was associated with a 61% lower risk of hospitalization (adjusted hazard ratio [aHR], 0.39; 95% confidence interval [CI], 0.18 to 0.85).

During a 90-day follow up, 208 patients (2.8%) experienced long-COVID symptoms that prompted them to see a physician. Paxlovid was associated with a 58% reduced risk of developing such symptoms during that period (aHR. 0.42; 95% CI, 0.19 to 0.95).

New England Journal Editorial

The editors of the failed symptom-based study published 2 weeks ago in the NEJM that started this whole post did try to contextualize the results with an editorial. They wrote that this study supports the current narrow indication for Paxlovid “only for persons who are at high risk for disease progression.” Then they pivoted to a question that a small study cannot answer: “What about treating people who have risk factors for severe Covid-19 but have received SARS-CoV-2 vaccines?” The editorial scraped up the bits of data from the small subgroup of patients who were actually at higher risk but vaccinated and started to cast shade on treatment in general before managing this redeeming statement:

Thus, it appears reasonable to recommend nirmatrelvir–ritonavir primarily for the treatment of Covid-19 in older patients (particularly those ≥65 years of age), those who are immunocompromised, and those who have conditions that substantially increase the risk of severe Covid-19, regardless of previous vaccination or infection status.

But the most true line is the concluding one:

Finally, we should require longer-term follow-up of participants in trials to determine whether the treatment of acute infection prevents post–Covid-19 conditions. Although we have learned an amazing amount about SARS-CoV-2 therapy, the final chapters on treating Covid-19 are yet to be written.

Thinking big, not small

I plan to keep prescribing Paxlovid to those patients who want it, strongly recommending it to high risk patients, and recommending it with caveats and unknowns explained to those younger, healthier patients at higher risk of long Covid. If older, high risk patients have contraindications and medication interactions, I’ll talk about alternative antivirals. I like the 90% viral load reduction with Paxlovid, and I’ll stick with my intuition that lower viral loads are still good for reducing risks of all kinds of outcomes. Obliteration of congestion and cough and acute symptoms are the least of my many concerns with Covid. And a 5 day treatment course is probably not long enough. There is already evidence that 5 days of molnupiravir is not enough, and that we should be studying 10.

Treating strep throat with antibiotics only hastens resolution of sore throat symptoms a little, but that’s not the primary reason why we prescribe it. The benefit of treatment is the proven reduction in rheumatic fever, i.e. the “severe disease” of strep throat. This took a long time to become standard of care. While the link between strep infections and rheumatic fever was recognized earlier, it took around 20 years from the late 1920s to the late 1940s for clinical studies to definitively prove that prompt penicillin treatment for strep throat could dramatically reduce the risk of developing rheumatic fever complications. This became standard practice by the 1950s.

Treating shingles with antivirals like valacyclovir doesn’t do much to alleviate the horrible pain or duration of shingles. Rather we use it for the reduction in long lasting or permanent pain and nerve damage called post-herpetic neuralgia (PHN). While antivirals were available in the 1980s, it took until the mid-1990s for clear evidence of their ability to prevent PHN when given early for shingles. The greatest benefits were seen with the more potent antivirals like valacyclovir in the early 2000s, nearly 20 years after the first antiviral drugs emerged. Early treatment within 72 hours was found to be critical for preventing PHN.

Treating influenza with antivirals like oseltamivir (Tamiflu) probably reduces the risk of cardiovascular events after flu illness by 60% in people with heart disease. A study published in Circulation examined electronic healthcare and pharmacy records of 37,482 TRICARE beneficiaries aged 18 and older with a history of cardiovascular disease and a subsequent influenza diagnosis between 2003 and 2007, grouping them based on whether they received oseltamivir within 2 days of the influenza diagnosis. The incidence of recurrent cardiovascular events within 30 days after the influenza diagnosis was 8.5% for the oseltamivir-treated group and 21.2% for the untreated group (a 60% reduction in risk).

Conclusion, written in a conversational style after a long damn slog of a post

Paxlovid, thanks for all you’ve done to help us against coronaviruses. You still jam up their protease enzymes, making it difficult for them to reproduce billions of zombie clones in our bodies, and when started early enough you reduce viral load by 90%. I know you often taste quite bad, and can upset stomachs, and are generally a pain to prescribe with other complicated medications… but you still have value, proven and speculative. You are no longer a superstar because people are doing better with Covid infections, but many still are not, especially those at high risk. Excess mortality rates are still climbing so there is a lot of data we are not capturing, and in my little office I still see the cumulative toll Covid is having on people. I want to help any way I can, including prevention and treatment. I’ll keep offering you to sick patients, especially those who are older, at higher risk of hospitalization and death, at higher risk of long Covid, the immunocompromised, and anyone who is thinking about taking ivermectin horse dewormer instead. Sure, you make money for a big pharma company, but you can’t help that, and they really aren’t the enemy here. Covid is. Speaking of money, did you hear that baseball player Shohei Ohtani is set to make $700 million dollars over 10 years? It would take me 47,000 years of writing this Substack to match that! I always appreciate everyone who supports it though.

~

Take good care. Best of luck, wisdom, and knowledge in making your own treatment decisions, you know, with your doctor :)

Thank you Ryan, Some of these recent articles and comments on Paxlovid have been worrisome. The closer look you guide us through helped greatly to clarify the evidence. If I get covid I would want Paxlovid; probably 10 days.

Marty (aka old, therefor high risk, retired Pulmonary/Critical Care doc).

I had to share this comment from another site I cross posted to... I never heard of this, but it may prove prophetic, and either way it is a fascinating window into the machinations behind the science in some cases:

Commenter:

"4 years in the industry and 20 at FDA.

This looks like possible Life Cycle Management to me. [It may have a new name now. Renaming existing ideas is faster and cheaper than coming up with new ideas.]

To be absolutely clear, LCM is practiced industrywide. No company has a monopoly on it, all companies do it to a greater or lesser extent, because our regulations allow it. It has a limited number of fairly predictable moves, once you’ve seen how it works.

Note the affiliation of all the authors, and the study site.

Note the relatively small n and the ITT — sorry, intent to treat analysis — that guarantees a high dropout rate will strongly bias results against the drug. When people drop out after one dose, the last observation carried forward is not going to be friendly to the drug, unless they all dropped out because they were instantaneously healed. By the way, that kind of thing — early dropouts due to high efficacy — has actually been seen, and studies are then terminated early for ethical reasons [not leaving people on placebo when there is no further need for a placebo group].

Note the study population.

Note the publication in a top tier journal and the interesting tendency of the audience to “turn on” the drug uncritically. Are there “thought leaders” among those critics? I didn’t work in that area, I wouldn’t know the names. But I wouldn’t be surprised if there are.

Based on prior experience with how LCM works, I will be quite surprised if we don’t see press releases about a theoretical successor drug soon. They may even already be out there.

I’d guess there might be requests for fast track development and then for priority review. And if I were a betting woman, I’d bet on requests for acceptance of one large Phase 2 study performed at two sites in lieu of a Phase III study.

Non-US sites may be used. It’s obnoxious to send inspectors out to them. And studies conducted entirely outside the US are not generally registered with clinicaltrials.gov. clinicaltrials.gov/...

If LCM works as intended the new product will also cost much more than the original treatment, which will be withdrawn from the market shortly after the successor is approved, for “business reasons”.

Again, these are standard LCM type moves industrywide nowadays. Keep that in mind.

Also, one can reconstruct the trajectory I’ve predicted by looking at a company’s press releases, blurbs about new drugs in development that appear in the trade press, and, once approved, the clinical trials section of the package insert. Companies brag about fast track development and priority review, so the press releases will usually confirm if these happen. Publications related to the pivotal trials will indicate study sites. Thus, none of these predictions impinges on anything that could be considered trade secret.

The next link talks about what an interested reader can glean from the clinical trials section of an approved drug’s package insert… www.pharmacytimes.com/…

And once more I will reiterate: this is standard operating procedure. I personally am no fan, since the time pressures involved do mean that problems are not always caught during the trial stage. Sometimes a drug will be taken off the market post approval because the smaller, faster studies did not include enough people to detect a particular side effect.

But this is how drug development unfolds in the US nowadays."